This is one in a series about touring Massachusetts and Newport, Rhode Island. My husband and I spent three weeks there in October, 2021. This Travelogue is a journal of our trip, done for my own sake and to show readers why you should visit Massachusetts.

When I visited Orchard House in Concord, I discovered that Louisa’s life was even more interesting than Jo’s in Little Women. I bought some books from their wonderful gift store and am sharing some of what I learned here.

The Concord Homes

There are two homes in Concord that include the history of the Alcott’s: The Wayside (called Hillside by the Alcotts) and Orchard House. The Wayside is the home where Louisa and her sisters spent seven happy years (1845-1852) living many of the childhood adventures described in Little Women. Unfortunately it is currently closed, likely due to Covid-etc.

Orchard House is the home Louisa’s parents lived in for 25 years. Louisa and her sisters, Anna (Meg) and May (Amy), lived there sporadically. Beth, however, died before they moved in. Louisa preferred living in Boston where she could be alone to write, attend lectures and the theatre, or act in theatricals. She left Orchard House and returned to Boston whenever she felt the family could do without her.

About Louisa’s Father – Amos Bronson Alcott

Hillside (The Wayside) was actually kept in trust by the brother of Mrs. Abigail May Alcott (Marmee), as well as her cousin. Abigail had purchased the home through an inheritance from her father. This arrangement was made to protect the house from her husband’s many creditors; Amos Bronson Alcott was perpetually in debt from his refusal to earn a practical living. Completely devoted to transcendental philosophy, which he helped create, Alcott tried to spread the word–like a pebble in a pond.

Throughout his life Alcott opened schools for children that closed after parents learned more about his controversial teachings. For instance, Alcott wrote that if a child ate the “wrong” foods or overate in general ” . . . the brow comes down, and the head grows out back, instead of growing high towards heaven, and the hands begin to scratch, and there is quarreling.” Even worse from a Puritan point-of-view, Alcott stated in the book Conversations with Children on the Gospels, that “It is the mission of this age . . . to reproduce Perfect Men.” The last thing Puritan parents wanted was for their children to have conversations about reproduction. (Alcott believed that in order to produce children free of original sin, sex must take place without passion. This belief came after he had fathered five children of his own; a son died at birth)

Fruitlands

When he wasn’t teaching, Bronson Alcott traveled to learn, and spread the word, about Transcendentalism. Many of his ideas were praiseworthy, such as ending slavery, rights for Native Americans, and equality for women. A vegan before the term existed, he refused to eat meat or use animal labor. In 1843, these beliefs blossomed–and failed miserably–on a farm they named Fruitlands. Residing on 100 acres of land, the Fruitlands residents (all thirteen of them) attempted to farm without the use of animal labor, and live without animal products (i.e. whale oil for lamps, wool and leather for clothing). The men also didn’t believe in working for wages. At various times they left the farm to travel and preach, gladly accepting free transportation and shelter from people who did believe in earning money. During these sojourns, they left Alcott’s wife and young daughters to harvest most of the crops. Eight months after it began, power struggles and the threat of starvation ended the Fruitlands experiment.

If you want to know more, Louisa May Alcott wrote a funny and revealing story about that time called Transcendental Wild Oats. There is also a book called Fruitlands by Richard Francis that tells the full story.

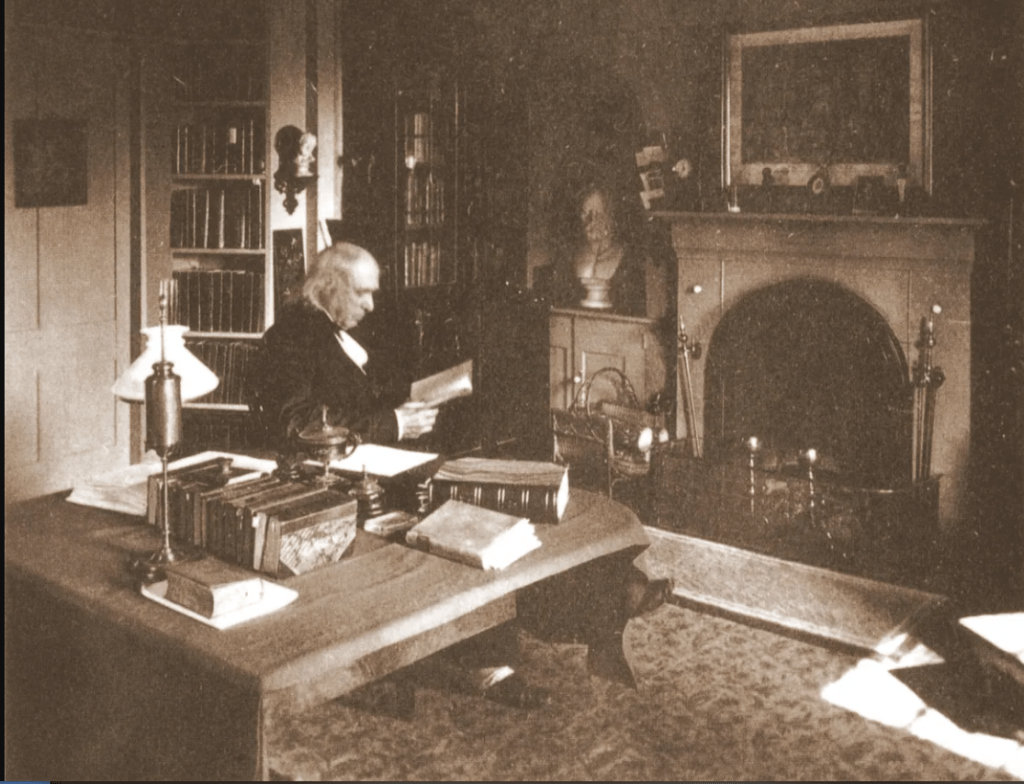

The Concord School of Philosophy

Finally, however, Alcott opened a successful school: The Concord Summer School of Philosophy–for adults only. In 1879, attendees met in Alcott’s study at Orchard House, but after a large donation from a NY philanthropist and financial help from Louisa, they moved the school to a barn-like structure on the Orchard property. The school became a huge success, and people attended from all over the world. It lasted for eight summers but closed with Alcott’s death in 1888 (he had stopped teaching after suffering a stroke in 1882).

Louisa Supported the Family

After the Fruitlands experiment, Louisa’s mother Abigail (Marmee) supported the family by working for charities that catered to the poor. As she aged however, her health gradually worsened. Louisa and her older sister Anna stepped in to earn as much as they could for the family. Both sisters taught, or worked as governesses. Louisa earned much of her money as a private seamstress. She also wrote stories that sold for a few dollars, but didn’t turn to full-time writing till her early 30’s. Her success as an author allowed her to pay off her father’s debts and provide for the family.

Louisa Worked as a Nurse during the Civil War

In December 1863, Louisa served as a nurse in a Georgetown, Washington D.C. hospital. She only worked for six weeks before becoming deathly ill with typhoid fever. As a result of that experience however, Louisa wrote Hospital Sketches and received positive acclaim from across the country. Unfortunately, Louisa never regained her full health after surviving typhoid, yet she went on to do her best writing.

Louisa Writes Little Women

In 1868, Louisa wrote Little Women through the request of her publisher. Until then she had not considered writing for girls as she felt she understood boys much better: “Never liked girls or knew many, except my sisters; but our queer plays and experiences may prove interesting, though I doubt it.” (Louisa May Alcott: Her Life, Letters, and Journals, Edited by Ednah Dow Cheney, page 199).

Little Women Based on Real Life

Louisa wrote a statement comparing Little Women to her real life –

“Facts in the stories that are true, though often changed as to time and place: The early plays and experiences; Beth’s death; Jo’s literary and Amy’s artistic experiences; Meg’s happy home; . . . Mr. March did not go to the war, but Jo did. Mrs. March is all true, only not half good enough. Laurie is not an American boy, though every lad I ever knew claims the character. He was a Polish boy, met abroad in 1865. Mr. Lawrence is my grandfather, Colonel Joseph May. Aunt March is no one.” (Louisa May Alcott, Her Life, Letters, and Journals, Edited by Ednah Dow Cheney, page 193)

Little Women earned Louisa world-wide fame. She now had the ability to completely provide for her family, who depended on her steady income. In fact, even when suffering from exhaustion, Louisa kept writing for the sake of her family. In April 1869 she wrote in her journal that “. . . the family seem so panic-stricken and helpless when I break down, that I try to keep the mill going.”

Louisa and May Were Very Close

The stormy relationship depicted in Little Women between Jo and Amy did not last. As they grew older, Louisa (Jo) and May (Amy) became very close. In many ways they were alike–independent, strong-willed, loving adventure, and possessing a good sense-of-humor. When typhoid fever confined a deathly-ill Louisa to her bedroom in the Orchard House, May tried to cheer her by painting directly on the walls of the room.

Louisa traveled with May and a friend to Europe, and later funded two more European trips for May so she could continue her artistic studies. Their letters and journal entries show the love and affection they had for each other.

May Alcott (Amy) Died Too Soon

May Alcott Nieriker – the real Amy in Little Women – became a well-respected artist but died before reaching her full potential. Fiercely independent, she did not marry till the age of 38, and then to a man sixteen years younger than she. Ernest Nieriker, from Switzerland, worked as a businessman. He was also an accomplished violinist. The two met in England while living at the same boarding house, and after marrying (March 11, 1878), settled down in the town of Meudon, near Paris. According to May’s letters home, she continued her trajectory as an artist while living a blissful married life with her new husband: “To be a happy wife with a good husband to love and care for me, and then go on with my art. This blessed lot is mine, and from my purpose I never intend to be diverted.” (May Alcott, A Memoir by Caroline Ticknor, page 278)

In the Spring, the prestigious Paris Salon accepted a second painting by May. “La Negresse” shows the maturity and loveliness of her style.

During the summer of 1878, May completed many projects, including oils, water colors, fourteen sketches, seven studies exhibited in Paris, a panel for the Manchester gallery in England, two panels for London, and an “order ready for America.” She and Ernest also awaited the birth of their first child. Though May anticipated the birth with great joy, she also prepared for the worst, packing her trunk with precious paintings, and sending a request to Louisa to raise her child if she died during child birth.

On November 8, 1879, Little Louisa (Lulu) came into the world, and for a short time all seemed well. May, however, came down with brain fever, likely caused by the doctors themselves as they did not know about germs and the necessity of hand washing. May succumbed on December 29. If she had lived, she likely would have become nearly as famous as her sister Louisa.

Louisa and Anna Raised Lulu

Arrangements were made to send little Lulu home to Louisa, who suffered from ill health but rallied for her precious niece. Lulu thrived under the care of her aunts, staying with Louisa, but going to Anna’s if Louisa felt ill. Lulu enjoyed the company of Anna’s two young sons as well. After Louisa died, Lulu’s father returned from Switzerland and brought his eight-year-old child back with him. I couldn’t find much information about Lulu except that she lived the rest of her life in Switzerland, married, and had a daughter. She died in 1975 at the age of 96.

Louisa May Have Had Lupus

In a scientific paper published in 2007, two doctors theorize that Louisa suffered from Lupus. Lupus is a disease where the victim’s immune system attacks your own body. After studying the symptoms described throughout Louisa’s journals and letters, as well as viewing a tell-tale facial rash on her portrait, they concluded that she likely succumbed to lupus. You can read more about their paper here. Louisa herself thought she suffered from mercury poisoning after being treated for typhoid fever in the Georgetown hospital. Louisa died on March 6, 1888. She is buried with her family in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Concord.

Visit the Orchard House

I highly recommend visiting the Orchard House located at 399 Lexington Road, Concord, MA. For fans of Little Women there is nothing like the feeling of seeing the desk where Louisa sat and wrote Little Women, viewing the boots she wore in her play-acting, peeking at Anna’s gray-silk wedding suit, sighing over Beth’s little piano, and wondering at May’s art. They have a wonderful book store as I said earlier, and guides who love their subject. For more information, check out their website.

Karen…This is a wonderful summary with such interesting historical references. Now I want to visit the Orchard House! Thank for you sharing your experience with us.

Karen, So interesting, thanks for sharing all this info. Very interesting. I will have Larry read too…he is such a history buff…. He will enjoy it. Great photos.

Tish

Thank you Tish! I’m so glad you found it worthwhile. Thanks for commenting.